How Would You Compare The Digestive System Of Animals

Compare and contrast dissimilar types of digestive systems

Animals obtain their diet from the consumption of other organisms. Depending on their diet, animals can be classified into the following categories: plant eaters (herbivores), meat eaters (carnivores), and those that swallow both plants and animals (omnivores). The nutrients and macromolecules present in food are non immediately accessible to the cells. In that location are a number of processes that change food within the animal body in club to make the nutrients and organic molecules accessible for cellular function. Every bit animals evolved in complexity of form and office, their digestive systems take also evolved to accommodate their various dietary needs.

Learning Objectives

- Place the different structures required for herbivory and predatory diets

- Compare and dissimilarity different types of digestive systems

- Explain the specialized functions of the organs involved in processing food in the body

Herbivores, Carnivores, and Omnivores

Herbivores are animals whose principal food source is establish-based. Examples of herbivores, equally shown in Figure ane include vertebrates similar deer, koalas, and some bird species, equally well every bit invertebrates such as crickets and caterpillars. These animals have evolved digestive systems capable of handling big amounts of found material. Herbivores can be further classified into frugivores (fruit-eaters), granivores (seed eaters), nectivores (nectar feeders), and folivores (leaf eaters).

Effigy 1. Herbivores, similar this (a) mule deer and (b) monarch caterpillar, eat primarily institute material. (credit a: modification of piece of work by Bill Ebbesen; credit b: modification of work by Doug Bowman)

Carnivores are animals that eat other animals. The word carnivore is derived from Latin and literally means "meat eater." Wild cats such as lions, shown in Figure 2a and tigers are examples of vertebrate carnivores, as are snakes and sharks, while invertebrate carnivores include sea stars, spiders, and ladybugs, shown in Effigy 2b. Obligate carnivores are those that rely entirely on creature flesh to obtain their nutrients; examples of obligate carnivores are members of the cat family unit, such as lions and cheetahs. Facultative carnivores are those that besides eat non-animal nutrient in addition to brute food. Notation that there is no clear line that differentiates facultative carnivores from omnivores; dogs would be considered facultative carnivores.

Figure ii. Carnivores similar the (a) king of beasts eat primarily meat. The (b) ladybug is also a carnivore that consumes minor insects called aphids. (credit a: modification of work by Kevin Pluck; credit b: modification of work by Jon Sullivan)

Omnivores are animals that consume both plant- and animal-derived food. In Latin, omnivore means to eat everything. Humans, bears (shown in Figure 3a), and chickens are example of vertebrate omnivores; invertebrate omnivores include cockroaches and crayfish (shown in Figure 3b).

Effigy 3. Omnivores like the (a) bear and (b) crayfish eat both plant and animal based nutrient. (credit a: modification of work past Dave Menke; credit b: modification of work by Jon Sullivan)

Invertebrate Digestive Systems

Animals take evolved different types of digestive systems to aid in the digestion of the different foods they consume. The simplest case is that of a gastrovascular cavity and is found in organisms with only 1 opening for digestion. Platyhelminthes (flatworms), Ctenophora (comb jellies), and Cnidaria (coral, jelly fish, and bounding main anemones) utilize this type of digestion. Gastrovascular cavities, as shown in Figure 4a, are typically a blind tube or crenel with merely 1 opening, the "mouth", which also serves equally an "anus". Ingested textile enters the mouth and passes through a hollow, tubular cavity. Cells within the cavity secrete digestive enzymes that pause down the food. The food particles are engulfed by the cells lining the gastrovascular cavity.

The alimentary culvert, shown in Figure 4b, is a more advanced system: it consists of one tube with a mouth at one end and an anus at the other. Earthworms are an case of an brute with an alimentary canal. Once the food is ingested through the mouth, it passes through the esophagus and is stored in an organ called the crop; then information technology passes into the gizzard where it is churned and digested. From the gizzard, the nutrient passes through the intestine, the nutrients are absorbed, and the waste is eliminated equally feces, called castings, through the anus.

Effigy 4. (a) A gastrovascular cavity has a single opening through which food is ingested and waste matter is excreted, as shown in this hydra and in this jellyfish medusa. (b) An gastrointestinal tract has two openings: a mouth for ingesting nutrient, and an anus for eliminating waste, equally shown in this nematode.

Vertebrate Digestive Systems

Vertebrates have evolved more complex digestive systems to accommodate to their dietary needs. Some animals have a unmarried tum, while others have multi-chambered stomachs. Birds take developed a digestive organization adapted to eating unmasticated nutrient.

Monogastric: Single-chambered Stomach

As the give-and-take monogastric suggests, this blazon of digestive system consists of one ("mono") stomach bedchamber ("gastric"). Humans and many animals accept a monogastric digestive system as illustrated in Figure 5a and 5b. The process of digestion begins with the mouth and the intake of food. The teeth play an important role in masticating (chewing) or physically breaking downwardly nutrient into smaller particles. The enzymes present in saliva also brainstorm to chemically break down nutrient. The esophagus is a long tube that connects the oral cavity to the stomach. Using peristalsis, or wave-similar smooth muscle contractions, the muscles of the esophagus push the food towards the tum. In order to speed upwards the actions of enzymes in the tummy, the stomach is an extremely acidic environment, with a pH betwixt 1.five and ii.five. The gastric juices, which include enzymes in the tummy, act on the food particles and continue the process of digestion. Further breakup of food takes identify in the pocket-size intestine where enzymes produced by the liver, the small intestine, and the pancreas continue the process of digestion. The nutrients are absorbed into the blood stream across the epithelial cells lining the walls of the small-scale intestines. The waste product cloth travels on to the big intestine where water is captivated and the drier waste fabric is compacted into feces; it is stored until it is excreted through the rectum.

Figure 5. (a) Humans and herbivores, such as the (b) rabbit, have a monogastric digestive organization. However, in the rabbit the minor intestine and cecum are enlarged to allow more fourth dimension to digest establish cloth. The enlarged organ provides more surface expanse for absorption of nutrients. Rabbits digest their nutrient twice: the first time food passes through the digestive system, it collects in the cecum, and then it passes every bit soft feces called cecotrophes. The rabbit re-ingests these cecotrophes to further digest them.

Avian

Birds confront special challenges when it comes to obtaining nutrition from food. They exercise not have teeth and and so their digestive organization, shown in Figure half-dozen, must be able to process united nations-masticated food. Birds have evolved a variety of nib types that reverberate the vast diversity in their diet, ranging from seeds and insects to fruits and nuts. Because most birds fly, their metabolic rates are high in order to efficiently procedure nutrient and keep their torso weight low. The stomach of birds has 2 chambers: the proventriculus, where gastric juices are produced to assimilate the food earlier it enters the tummy, and the gizzard, where the food is stored, soaked, and mechanically ground. The undigested material forms nutrient pellets that are sometimes regurgitated. Nigh of the chemical digestion and absorption happens in the intestine and the waste is excreted through the cloaca.

Effigy 6. The avian esophagus has a pouch, called a crop, which stores food.

In the avian digestive system, food passes from the crop to the first of two stomachs, called the proventriculus, which contains digestive juices that break downwardly food. From the proventriculus, the food enters the 2d stomach, called the gizzard, which grinds food. Some birds eat stones or grit, which are stored in the gizzard, to aid the grinding process. Birds do non have separate openings to excrete urine and feces. Instead, uric acid from the kidneys is secreted into the large intestine and combined with waste product from the digestive procedure. This waste is excreted through an opening chosen the cloaca.

Avian Adaptations

Birds have a highly efficient, simplified digestive arrangement. Contempo fossil prove has shown that the evolutionary divergence of birds from other land animals was characterized by streamlining and simplifying the digestive organization. Unlike many other animals, birds practise not have teeth to chew their nutrient. In place of lips, they take abrupt pointy beaks. The horny beak, lack of jaws, and the smaller tongue of the birds can be traced back to their dinosaur ancestors. The emergence of these changes seems to coincide with the inclusion of seeds in the bird nutrition. Seed-eating birds have beaks that are shaped for grabbing seeds and the 2-compartment stomach allows for delegation of tasks. Since birds need to remain lite in order to fly, their metabolic rates are very high, which means they digest their food very speedily and need to eat often. Contrast this with the ruminants, where the digestion of plant affair takes a very long fourth dimension.

Ruminants

Ruminants are mainly herbivores like cows, sheep, and goats, whose entire diet consists of eating large amounts of roughage or fiber. They have evolved digestive systems that assist them digest vast amounts of cellulose. An interesting feature of the ruminants' mouth is that they practise not accept upper incisor teeth. They use their lower teeth, tongue and lips to tear and chew their food. From the mouth, the nutrient travels to the esophagus and on to the stomach.

To help assimilate the large amount of plant material, the stomach of the ruminants is a multi-chambered organ, as illustrated in Figure 7. The four compartments of the stomach are chosen the rumen, reticulum, omasum, and abomasum. These chambers contain many microbes that break down cellulose and ferment ingested food. The abomasum is the "true" stomach and is the equivalent of the monogastric tummy bedroom where gastric juices are secreted. The four-compartment gastric bedchamber provides larger space and the microbial support necessary to digest plant material in ruminants. The fermentation process produces big amounts of gas in the tum chamber, which must be eliminated. As in other animals, the small-scale intestine plays an important function in nutrient absorption, and the big intestine helps in the elimination of waste material.

Figure vii. Ruminant animals, such as goats and cows, have four stomachs. The commencement two stomachs, the rumen and the reticulum, contain prokaryotes and protists that are able to assimilate cellulose fiber. The ruminant regurgitates cud from the reticulum, chews information technology, and swallows it into a third stomach, the omasum, which removes water. The cud then passes onto the fourth stomach, the abomasum, where it is digested by enzymes produced by the ruminant.

Pseudo-ruminants

Some animals, such as camels and alpacas, are pseudo-ruminants. They eat a lot of plant material and roughage. Digesting plant material is not piece of cake because institute cell walls contain the polymeric sugar molecule cellulose. The digestive enzymes of these animals cannot pause down cellulose, just microorganisms present in the digestive organization tin can. Therefore, the digestive system must exist able to handle large amounts of roughage and break downward the cellulose. Pseudo-ruminants accept a iii-chamber stomach in the digestive system. However, their cecum—a pouched organ at the beginning of the large intestine containing many microorganisms that are necessary for the digestion of institute materials—is big and is the site where the roughage is fermented and digested. These animals do not take a rumen merely have an omasum, abomasum, and reticulum.

Parts of the Digestive System

The vertebrate digestive system is designed to facilitate the transformation of food affair into the food components that sustain organisms.

Oral Crenel

The oral crenel, or mouth, is the betoken of entry of food into the digestive system, illustrated in Figure 8. The food consumed is broken into smaller particles by mastication, the chewing activeness of the teeth. All mammals have teeth and can chew their food.

Figure 8. Digestion of food begins in the (a) oral crenel. Food is masticated by teeth and moistened by saliva secreted from the (b) salivary glands. Enzymes in the saliva begin to assimilate starches and fats. With the assist of the tongue, the resulting bolus is moved into the esophagus by swallowing. (credit: modification of work by the National Cancer Plant)

The extensive chemical process of digestion begins in the mouth. Every bit food is being chewed, saliva, produced by the salivary glands, mixes with the food. Saliva is a watery substance produced in the mouths of many animals. In that location are three major glands that secrete saliva—the parotid, the submandibular, and the sublingual. Saliva contains mucus that moistens nutrient and buffers the pH of the food. Saliva also contains immunoglobulins and lysozymes, which have antibacterial action to reduce molar decay by inhibiting growth of some bacteria.

Saliva also contains an enzyme called salivary amylase that begins the procedure of converting starches in the food into a disaccharide called maltose. Another enzyme called lipase is produced by the cells in the tongue. Lipases are a grade of enzymes that can suspension down triglycerides. The lingual lipase begins the breakdown of fatty components in the food.

The chewing and wetting action provided by the teeth and saliva ready the nutrient into a mass called the bolus for swallowing. The natural language helps in swallowing—moving the bolus from the mouth into the pharynx. The pharynx opens to two passageways: the trachea, which leads to the lungs, and the esophagus, which leads to the tum. The trachea has an opening called the glottis, which is covered by a cartilaginous flap called the epiglottis. When swallowing, the epiglottis closes the glottis and food passes into the esophagus and non the trachea. This arrangement allows nutrient to be kept out of the trachea.

Esophagus

Figure 9. The esophagus transfers food from the mouth to the stomach through peristaltic movements.

The esophagus is a tubular organ that connects the oral fissure to the breadbasket. The chewed and softened food passes through the esophagus afterward existence swallowed. The smooth muscles of the esophagus undergo a series of wave like movements chosen peristalsisthat push button the food toward the breadbasket, as illustrated in Figure nine. The peristalsis moving ridge is unidirectional—information technology moves nutrient from the oral fissure to the stomach, and reverse movement is non possible. The peristaltic movement of the esophagus is an involuntary reflex; it takes place in response to the act of swallowing.

A ring-similar musculus called a sphincter forms valves in the digestive organisation. The gastro-esophageal sphincter is located at the breadbasket end of the esophagus. In response to swallowing and the pressure exerted by the bolus of nutrient, this sphincter opens, and the bolus enters the stomach. When in that location is no swallowing activity, this sphincter is shut and prevents the contents of the breadbasket from traveling upward the esophagus. Many animals have a true sphincter; nonetheless, in humans, there is no truthful sphincter, but the esophagus remains closed when there is no swallowing activity. Acid reflux or "heartburn" occurs when the acidic digestive juices escape into the esophagus.

Stomach

A large role of digestion occurs in the stomach, shown in Figure x. The stomach is a saclike organ that secretes gastric digestive juices. The pH in the stomach is between i.5 and 2.5. This highly acidic environment is required for the chemical breakdown of food and the extraction of nutrients. When empty, the stomach is a rather minor organ; yet, it tin can expand to up to xx times its resting size when filled with food. This characteristic is particularly useful for animals that need to eat when food is available.

Figure 10. The human stomach has an extremely acidic environs where almost of the protein gets digested. (credit: modification of work by Mariana Ruiz Villareal)

Practice Question

Which of the following statements almost the digestive system is false?

- Chyme is a mixture of nutrient and digestive juices that is produced in the tummy.

- Nutrient enters the large intestine before the small intestine.

- In the small intestine, chyme mixes with bile, which emulsifies fats.

- The stomach is separated from the small-scale intestine by the pyloric sphincter.

Testify Answer

Argument b is truthful.

The tummy is as well the major site for protein digestion in animals other than ruminants. Protein digestion is mediated by an enzyme chosen pepsin in the tummy chamber. Pepsin is secreted by the primary cells in the breadbasket in an inactive course called pepsinogen. Pepsin breaks peptide bonds and cleaves proteins into smaller polypeptides; it also helps activate more than pepsinogen, starting a positive feedback mechanism that generates more pepsin. Some other prison cell blazon—parietal cells—secrete hydrogen and chloride ions, which combine in the lumen to form hydrochloric acrid, the master acidic component of the breadbasket juices. Muriatic acid helps to convert the inactive pepsinogen to pepsin. The highly acidic environment also kills many microorganisms in the food and, combined with the action of the enzyme pepsin, results in the hydrolysis of protein in the food. Chemic digestion is facilitated by the churning action of the tum. Contraction and relaxation of smooth muscles mixes the stomach contents about every 20 minutes. The partially digested food and gastric juice mixture is called chyme. Chyme passes from the stomach to the small intestine. Further protein digestion takes identify in the small intestine. Gastric emptying occurs inside 2 to six hours after a meal. Only a small amount of chyme is released into the small intestine at a time. The motion of chyme from the stomach into the modest intestine is regulated by the pyloric sphincter.

When digesting protein and some fats, the stomach lining must be protected from getting digested past pepsin. There are two points to consider when describing how the tummy lining is protected. Get-go, as previously mentioned, the enzyme pepsin is synthesized in the inactive class. This protects the chief cells, because pepsinogen does not have the same enzyme functionality of pepsin. Second, the tummy has a thick mucus lining that protects the underlying tissue from the action of the digestive juices. When this mucus lining is ruptured, ulcers can course in the stomach. Ulcers are open wounds in or on an organ caused by bacteria (Helicobacter pylori) when the mucus lining is ruptured and fails to reform.

Minor Intestine

Chyme moves from the stomach to the pocket-sized intestine. The small intestine is the organ where the digestion of protein, fats, and carbohydrates is completed. The pocket-sized intestine is a long tube-similar organ with a highly folded surface containing finger-like projections chosen the villi. The apical surface of each villus has many microscopic projections chosen microvilli. These structures, illustrated in Figure 11, are lined with epithelial cells on the luminal side and allow for the nutrients to be captivated from the digested food and absorbed into the claret stream on the other side. The villi and microvilli, with their many folds, increase the surface area of the intestine and increase absorption efficiency of the nutrients. Absorbed nutrients in the blood are carried into the hepatic portal vein, which leads to the liver. At that place, the liver regulates the distribution of nutrients to the residual of the trunk and removes toxic substances, including drugs, booze, and some pathogens.

Figure 11. Villi are folds on the pocket-sized intestine lining that increment the surface expanse to facilitate the assimilation of nutrients.

Practise Question

Which of the post-obit statements well-nigh the small intestine is false?

- Absorptive cells that line the pocket-sized intestine accept microvilli, minor projections that increase surface surface area and assistance in the absorption of food.

- The inside of the minor intestine has many folds, called villi.

- Microvilli are lined with blood vessels as well every bit lymphatic vessels.

- The within of the small intestine is called the lumen.

Evidence Respond

Statement c is false.

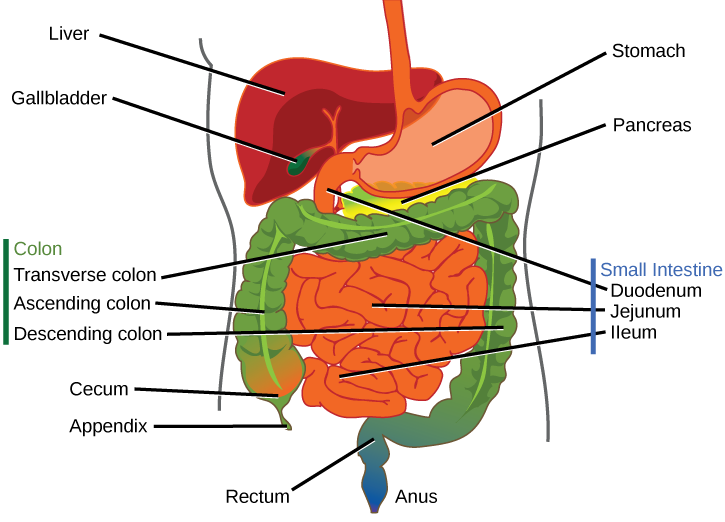

The homo modest intestine is over 6m long and is divided into three parts: the duodenum, the jejunum, and the ileum. The "C-shaped," fixed function of the small intestine is called the duodenum and is shown in Effigy 10. The duodenum is separated from the tum past the pyloric sphincter which opens to let chyme to move from the breadbasket to the duodenum. In the duodenum, chyme is mixed with pancreatic juices in an alkaline solution rich in bicarbonate that neutralizes the acidity of chyme and acts equally a buffer. Pancreatic juices also contain several digestive enzymes. Digestive juices from the pancreas, liver, and gallbladder, as well as from gland cells of the intestinal wall itself, enter the duodenum. Bile is produced in the liver and stored and concentrated in the gallbladder. Bile contains bile salts which emulsify lipids while the pancreas produces enzymes that catabolize starches, disaccharides, proteins, and fats. These digestive juices break down the nutrient particles in the chyme into glucose, triglycerides, and amino acids. Some chemical digestion of food takes place in the duodenum. Assimilation of fat acids besides takes place in the duodenum.

The second role of the small intestine is called the jejunum, shown in Figure ten. Hither, hydrolysis of nutrients is connected while most of the carbohydrates and amino acids are captivated through the intestinal lining. The bulk of chemical digestion and nutrient absorption occurs in the jejunum.

The ileum, also illustrated in Figure ten is the terminal part of the pocket-sized intestine and hither the bile salts and vitamins are absorbed into blood stream. The undigested food is sent to the colon from the ileum via peristaltic movements of the muscle. The ileum ends and the big intestine begins at the ileocecal valve. The vermiform, "worm-like," appendix is located at the ileocecal valve. The appendix of humans secretes no enzymes and has an insignificant part in amnesty.

Large Intestine

Effigy 12. The large intestine reabsorbs h2o from undigested food and stores waste matter material until it is eliminated.

The large intestine, illustrated in Effigy 12, reabsorbs the water from the undigested food textile and processes the waste cloth. The human large intestine is much smaller in length compared to the minor intestine simply larger in diameter. It has three parts: the cecum, the colon, and the rectum. The cecum joins the ileum to the colon and is the receiving pouch for the waste product affair. The colon is dwelling to many bacteria or "intestinal flora" that aid in the digestive processes. The colon tin can exist divided into 4 regions, the ascending colon, the transverse colon, the descending colon and the sigmoid colon. The main functions of the colon are to excerpt the water and mineral salts from undigested food, and to store waste textile. Carnivorous mammals take a shorter large intestine compared to herbivorous mammals due to their diet.

Rectum and Anus

The rectum is the concluding terminate of the large intestine, every bit shown in Effigy 12. The primary office of the rectum is to shop the feces until defecation. The carrion are propelled using peristaltic movements during emptying. The anus is an opening at the far-end of the digestive tract and is the exit point for the waste material. Two sphincters between the rectum and anus control elimination: the inner sphincter is involuntary and the outer sphincter is voluntary.

Accompaniment Organs

The organs discussed above are the organs of the digestive tract through which food passes. Accessory organs are organs that add secretions (enzymes) that catabolize food into nutrients. Accessory organs include salivary glands, the liver, the pancreas, and the gallbladder. The liver, pancreas, and gallbladder are regulated by hormones in response to the nutrient consumed.

The liver is the largest internal organ in humans and it plays a very of import part in digestion of fats and detoxifying blood. The liver produces bile, a digestive juice that is required for the breakdown of fat components of the food in the duodenum. The liver too processes the vitamins and fats and synthesizes many plasma proteins.

The pancreas is another of import gland that secretes digestive juices. The chyme produced from the breadbasket is highly acidic in nature; the pancreatic juices contain loftier levels of bicarbonate, an alkali that neutralizes the acidic chyme. Additionally, the pancreatic juices comprise a large diversity of enzymes that are required for the digestion of poly peptide and carbohydrates.

The gallbladder is a small organ that aids the liver past storing bile and concentrating bile salts. When chyme containing fatty acids enters the duodenum, the bile is secreted from the gallbladder into the duodenum.

In Summary: Parts of the Digestive Arrangement

Many organs work together to digest nutrient and absorb nutrients. The oral cavity is the point of ingestion and the location where both mechanical and chemical breakup of food begins. Saliva contains an enzyme called amylase that breaks down carbohydrates. The nutrient bolus travels through the esophagus by peristaltic movements to the stomach. The stomach has an extremely acidic surround. An enzyme called pepsin digests poly peptide in the stomach. Further digestion and absorption take place in the small-scale intestine. The big intestine reabsorbs h2o from the undigested food and stores waste matter until elimination.

Check Your Agreement

Respond the question(s) below to see how well you sympathise the topics covered in the previous section. This short quiz doesnot count toward your grade in the class, and you lot tin can retake information technology an unlimited number of times.

Use this quiz to check your understanding and determine whether to (ane) study the previous section further or (2) move on to the next section.

Source: https://courses.lumenlearning.com/suny-wmopen-biology2/chapter/digestive-systems/

Posted by: whatleyephimagent.blogspot.com

0 Response to "How Would You Compare The Digestive System Of Animals"

Post a Comment